That’s what I’m doing and that’s what I want to keep doing.’ I’ve kind of posted that in my office now. Once I read him saying that, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh. Social thrillers is a description I started to use after hearing Jordan Peele describe Get Out that way. But my niche is writing sort of hard-hitting thrillers.

There are people who write contemporary fun stuff and humor for kids, which they eat up. I think there’s absolutely a place for that. There are plenty of other writers who write escapist fantasies and I’ve written a little bit myself. They read books I wrote about the Holocaust and Hitler Youth and they said, ‘We want more.’ I already know from my own experience and my own previous books that kids really want to hear the truth about the world.

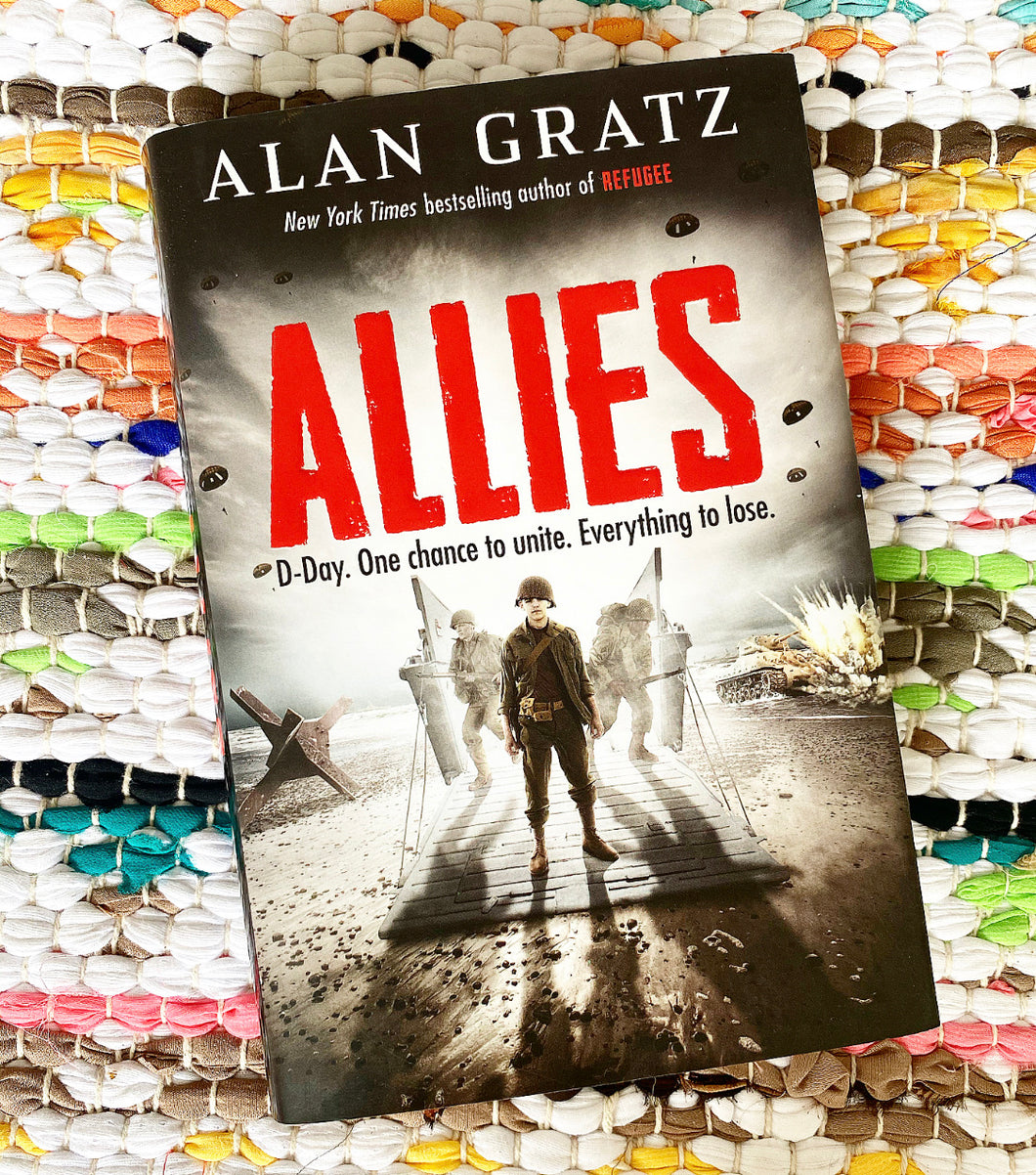

I talk to thousands of middle schoolers every year at schools. Most of my books have been aimed at middle graders, ages eight to fourteen. How do you think about the commercial appeal of your work and its value to both parents and kids? You were writing children’s books about the Holocaust even before the refugee crisis. Fatherly spoke to Gratz about how the book took shape and why he desperately wants American kids to read it. There’s Josef, a Jewish boy who is fleeing Nazi Germany in 1939, Isabel, a Cuban girl bound for America in 1994, and Mahmoud, a Syrian boy heading to modern Germany. Refugee tells the stories of three different child refugees at different points in history. It is the book he needed to write because he couldn’t keep reality or his own empathy at bay. But, painful as it can be to read, it is honest and, for Gratz, deeply personal. Before the fall is over, it will make some middle school reading lists and, subsequently, make some parents nervous. It is pitch dark and, unfortunately, incredibly timely. The book is about the people who have nowhere to go but elsewhere. Previously best known for Prisoner B-3087, a disturbing account of a Jewish boy’s time in ten Nazi concentration camps, and Samurai Shortstop, a heavier-than-it-sounds and hyper-violet depiction of pre-modern Japan, Gratz has just released Refugee. He is unafraid to go dark and frankly eager to uncover the horrors of history for an audience eager (if not ready) to grapple with them. He’s a children’s book author–and damn proud of it–but he’s largely indifferent to the norms of his genre. Alan Gratz isn’t particularly interested in anthropomorphizing animals or object lessons about sharing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)